By Ellen Byerrum

What if clothes were haunted like houses or locations?

Could a dress be toxic enough to kill?

How would someone dispatch a villain in a dying velvet factory?

These may not be the nicest of questions, but they are among ones I’ve asked myself when writing my Crime of Fashion Mysteries. I wrapped these ideas into the plots of three of the books, but not without looking further into these queries and their answers. While imagination plays the largest part in crafting a story, I also like to get it right, or at least have a realistic place to jump to the realm of make-believe.

That’s where research comes in. It can be one of the most enjoyable parts of writing. The hands-on research, that is, the kind that lifts you out of your chair and away from your desk.

Sure, there are a lot of facts at your fingertips via the Internet and Google. And like everyone else, I use my computer for finding information and checking details. However, the web is no substitute for leaving your comfort zone and meeting people, asking questions, or just walking around in the location about which you want to write. In the shoes of your characters, so to speak. However, in my case, it might also be in their dresses.

Where did my question about haunted clothing come from?

I once had the strangest experience of putting on one of my vintage 1940s suits and feeling very strongly that I was supposed to wear Chanel No. 5 with that suit. Chanel No. 5?! Was that a memory left behind by the original woman who owned the suit? Did she wear Chanel No. 5? I don’t particularly care for that fragrance, it’s a bit too sweet for me. But my husband thoughtfully bought me the perfume anyway. I haven’t tried saying, “Honey, the suit wants a diamond necklace to go with it.” Not yet, anyway. Unfortunately for my jewelry box, the suit only wanted the right perfume.

Nevertheless, the idea of a haunted garment—in my case a haunted shawl—started rumbling around in my brain, and I knew there could be a fascinating story there. There’s not a lot of information on the web about haunted clothes, and haunted clothing doesn’t seem to be a common occurrence, either in experience or literature. That question, however, led to one of the most delightful interviews I have ever had. I made an appointment and interviewed two gracious experts in the Costume Collections at the Smithsonian Museum of American History.

They had no tales of ghostly garments, although they had one item they called the “bad luck” bridal gown. (The bride died shortly after the wedding.) However, they offered me wonderful information about the collection, which has over 30,000 American garments which date from as early as the 1600s. I was able to view shoes, hats, dresses that the public will never get to see. I was so lucky and so grateful for their insights and I used some of that information for my ninth book, Veiled Revenge.

Deadly dyes and deadly dresses

Though not haunted, a deadly dress is something I explore in Lethal Black Dress, the tenth book in the series. I first heard about a dye known as “poison apple green” in a college class on the History of Costume (Liberal arts rock!) The toxic dye could be absorbed through the skin.

Years later, I worked my way through the literature on the phenomena and found that there were beautiful and brilliant blue and green colors that came from “Paris Green” dye. The dye was toxic, made from copper acetoarsenite, and was used in fabrics and paper, wallpaper and even candy wrappers. Unfortunately, when wet it released an arsenic gas, which could be absorbed through the pores. Some people believe that Napoleon died from arsenic poison emitted from his Paris Green wallpaper on the very humid island of St. Helena.

I consulted a doctor and asked whether such a dye really could kill someone. We tried out various scenarios while she pondered it and concluded, “Sure, why not?” That’s the beauty of fiction. Once you decide something is possible, you can wind yourself down a twisted trail of diabolical suspects and deadly plots, along with Paris Green dye.

And what about that velvet factory?

When I was a working journalist in Washington, D.C., a coworker told me the last velvet factory in Virginia (and the last dress-grade velvet factory in America) was going to close down, and that she knew the manager—I knew I had to see it for myself. I immediately called the manager and asked if I could tour the facility. I explained I was a reporter and a mystery writer, and he remarked, “Well, there are a lot of ways to kill people here.” Words that warm the cockles of a writer’s heart.

I took a day off work and traveled to the small economically depressed Virginia town.

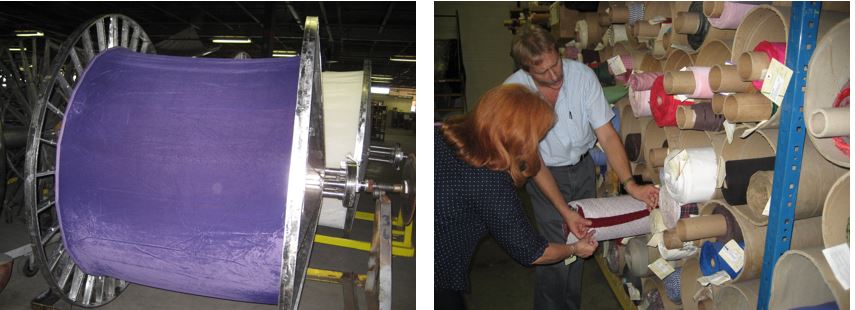

Bolts and bolts of shimmering fabric contrasted dramatically with the dangerous steel equipment required to manufacture it. Velvet is woven with two backing sheets at once, so that a razor-sharp blade must slice through the weave to release the soft velvet in the middle, creating two pieces of fabric. The circular blades used to cut it were at least six feet high.

Making velvet was not automated. Workers had to carefully pull and attach the material on racks with sharp steel teeth to stretch it and dry it. The velvet was then wound onto the teeth of giant spools to be dyed in massive tanks. Each step carried its own hazards.

Not only did I get a glimpse of what it would be like to work in such a factory (and how someone might meet their fictional fate there), I saw what closing the factory, the economic impact, meant to that small town. The factory once had a hundred weavers, but that function had been sent to England and the weaving room was now silent. Other departments were likewise decimated. When I visited there were just a handful of workers left.

It was a lot for me and my character Lacey Smithsonian to consider. That research was crucial in writing Shot Through Velvet, the seventh book in my series.

Ellen’s tour of the velvet factory

I am currently working on and researching a prequel to my series, which is set during World War II in Washington, D.C. It features Lacey’s great-aunt, Mimi Smith, when she was a young woman working for the wartime Office of Price Administration. In researching it, I have spent time visiting various D.C area locations, including Chinquapin Village, a housing development for Torpedo Factory workers. It was located in Alexandria, VA, but dismantled sometime after the war.

Research has a way of bringing things to life that otherwise might just be a heading on an outline. One question can lead you to people who have amazing insights, or to locations that can open up a whole world. It can make a story bigger and more involved. I recommend it.

Ellen Byerrum is a novelist, a playwright, a former Washington, D.C. journalist, and a graduate of private investigation school in Virginia. Her Screwball Noir Crime of Fashion mysteries feature Lacey Smithsonian, a reluctant fashion reporter in Washington, D.C., “The City That Fashion Forgot.” Lacey solves crimes with fashion clues while stylishly decked out in vintage togs.

Her most recent Crime of Fashion mystery, and the 11th in the series, is The Masque of the Red Dress. What do Russian espionage, Washington DC, and the theatre have in common? Spies, lies and a dangerous red dress.

Two of the COF novels, Killer Hair and Hostile Makeover, were filmed for the Lifetime Movie Network.

The Woman in the Dollhouse is Byerrum’s first suspense thriller. She has also penned a middle-grade mystery, The Children Didn’t See Anything, the first of stories starring the precocious 12-year-old Bresette twins, Evangeline and Raphael.

Under her playwright pen name, Eliot Byerrum, she has published two plays with Samuel French, A Christmas Cactus and Gumshoe Rendezvous.

You can find Ellen Byerrum on her website at www.ellenbyerrum.com.

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/EllenByerrumBooks/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/EllenByerrum

Ellen Byerrum’s Fashion Bites on YouTube: https://bit.ly/2OeYMPF

Buy The Masque of the Red Dress on Amazon: https://amzn.to/2LJUrCm

Very interesting blog, Ellen. I had no idea fabric and dyes etc. could be so lethal. Sounds like the research process yields many ideas for killing off your characters. (BTW – I sometimes like a few drops of Channel No. 5. But I also enjoy mysteries set in the 1940’s-50’s. ?)

So glad you enjoyed my post, Anne. Fabrics and fashions have so much information and yes, they provide me a lot of ideas, lethal and otherwise. I enjoy Chanel on other people, not as much on me. And I love mysteries set in other time periods. They can really bring other times and places to life. Cheers.

Welcome, Ellen. This is a fascinating post. Who knew fashion could be so dangerous?

It’s great to be here today, Maggie. And while some items should carry warning tags, other fashions are merely fascinating and fun. I’ll be splashing around in aqua aerobics this morning but I’ll check back in throughout the day. Thank you so much for inviting me!

A wonderful post, but so much intriguing information. I’m going to get started on your books!

You just made my day, Carol!

How fun! Thanks, Maggie, for introducing me to a new series. I know I’m going to love it.

Simon Doonan has an essay in one of his books about haunted vintage garments. As for poisoned clothing, my brain goes pronto to Marie de Medici ordering her glove maker to send arsenic-laced gloves to an enemy.

I must find that essay by Simon Doonan, Angela. Thanks for the tip.

Angela, I love the bit about the arsenic-laced gloves.

What a great post! I had no idea clothing could be so dangerous (luckily, I wear comfy pants and tees almost every day, so fashion is not my bailiwick. I love reading about it, though). Your research sounds fun, too. I’ve been to many of the Smithsonian museums, but not the textile one. It’s on my list for my next trip to DC. I’m definitely going to check out your books–they sound fantastic!

Thank you for your kind comments, Amy. There’s so much more to fashion than meets the eye. And yes my research is fun. I don’t think I could persevere without a dash of enjoyment.

Not only do your books sound like my type of reading, but I sincerely appreciate your humor. Are you sure the suit doesn’t want a diamond necklace?

It might, Perhaps I need to listen a little more closely! I’d like it if it also told me where to find the money to pay for it. Or where the original diamond necklace is. 🙂

Fascinating post. Thanks so much for sharing! This makes me reconsider how I see clothing & its dyes.

We can tell so much about people through their clothes. I’m glad you liked the post.

Hi Nikki, I have heard of the urban legend about the prom dress! Vaguely. I suppose the dress would have absorbed formaldehyde, which is in a lot of “sizing,” and has been classified a carcinogen.Some people could be very sensitive to that. But it would have been more interesting if the corpse’s dress had been exposed to some weird communicable disease. Okay, just thinking like a mystery writer! Thanks for your comment. I am so glad you’re looking forward to more books.

I’ve read some of the Lacey Smithsonian series and am so excited to see how many more I can anticipate — plus the Aunt Mimi book (series I hope) is eagerly anticipated. The “toxic dress” topic reminded me of an urban legend involving the reuse of a prom dress in which the previous owner had been embalmed—surely you’ve heard it. Thanks for your research and writing!